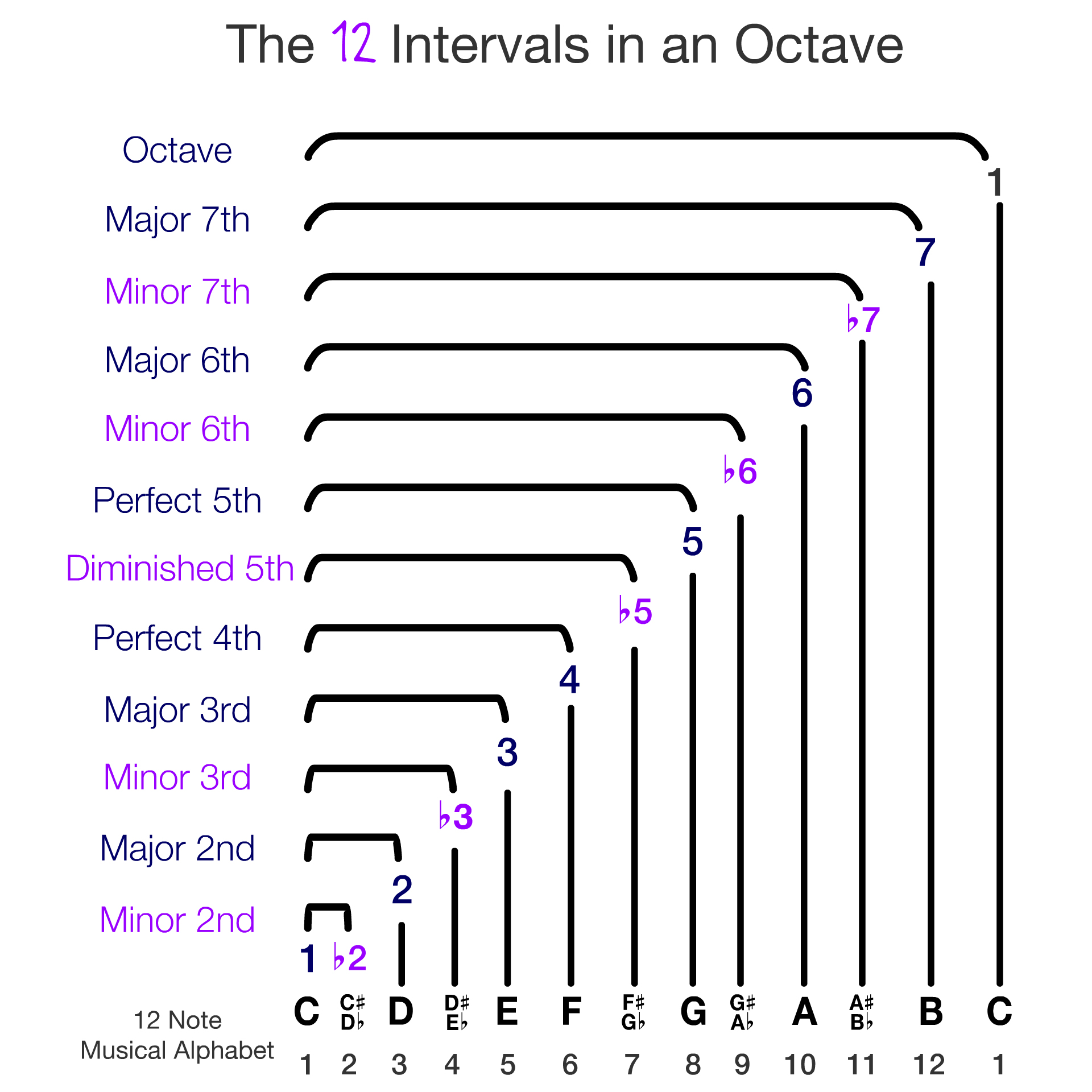

All 12 Intervals

To create the Major Scale we use a mixture of Whole Steps and Half Steps for our intervallic formula. Whenever a whole step is used, we are skipping over a note of the musical alphabet. Using the major scale formula, we are left with 7 unique notes and the first 7 intervals used in music theory. However, there is an interval for each of the 5 notes that we skipped over. These intervals are known as the minor intervals, though you will often see them written with a Flat symbol (♭) instead of writing out the word minor. This is because a minor interval is one half-step shorter than its major counterpart.

A minor interval is usually heard as a dark or sadder version of an interval. For example, using a minor 3 instead of a major 3 will dramatically make any scale or chord sound less bright or cheerful. Using a minor 7 instead of a major 7 will also have an edgier, darker sound. This is the same for all minor intervals.

You may have noticed a couple of inconsistencies here, namely with our “Perfect” intervals, the 4 and 5. Since both perfect intervals are the same in most major and minor scales, we don’t call them major or minor.

Here is a more in depth look at minor intervals:

It is possible to have a flat (♭) 5, though we consider it to be a “Diminished” interval rather than a minor. This is because once a scale or chord has this flat (♭) 5, it’s no longer minor; it has become a diminished scale/chord. This is a special interval that gets a little more advanced, so it’s better to save this info for a later lesson.

There is no flat (♭) 4. In the Major scale there is only a half step difference between the 3rd note and 4th note. This means that if we flat (♭) the 4th it won’t be a minor 4th, it will be a major 3rd! Not a dark sounding interval at all, in fact it’s probably the most major sounding interval there is! We can have a Sharp (#) 4 but it sounds identical to our diminished 5th.