The Modes

The Modes are, without a doubt, one of the most misunderstood subjects in all of music. They are also one of the most poorly taught subjects in all of music. Modes themselves shouldn’t be that confusing, or at least they shouldn’t be any more confusing than any other scale. After all, Modes are just scales.

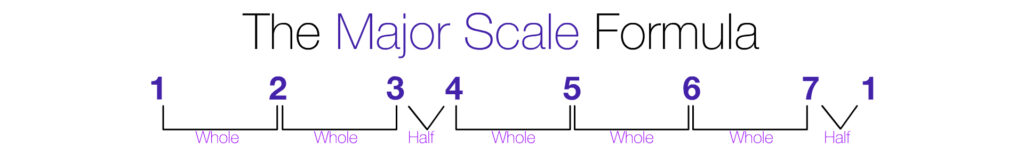

A scale is a group of notes that are organized through specific intervals or degrees. The intervals used will give each scale a particular sound or mood. The set of intervals used is called the scale formula. The Major Scale is famously Whole-Whole-Half-Whole-Whole-Whole-Half like so:

The Modes are standalone scales with their very own formulas. The confusion for the Modes arises because of how we derive or construct those formulas from the Major Scale.

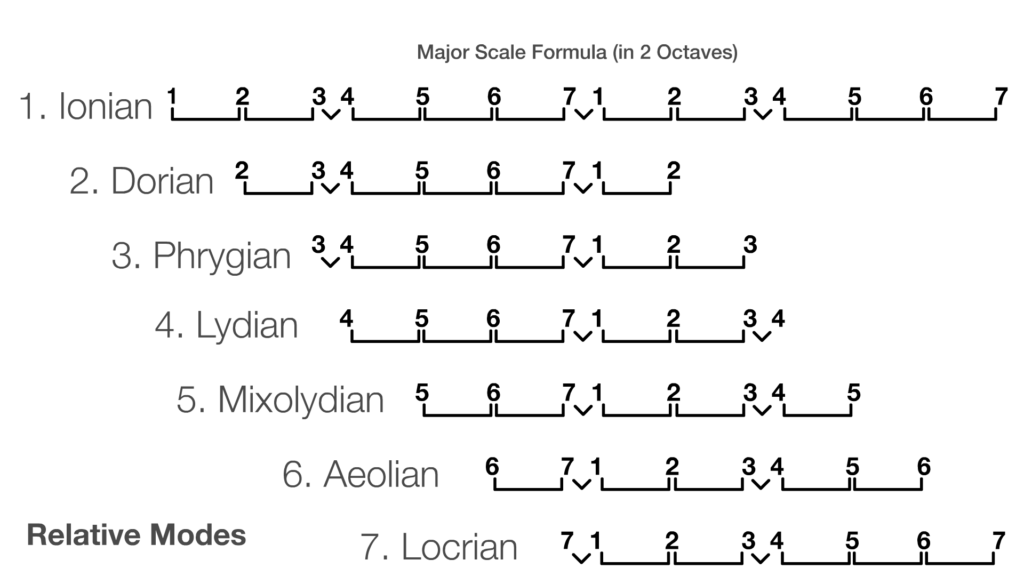

You may have seen this:

- Mode 1 – Ionian (The Major Scale)

- Mode 2 – Dorian

- Mode 3 – Phrygian

- Mode 4 – Lydian

- Mode 5 – Mixolydian

- Mode 6 – Aeolian (The Minor Scale)

- Mode 7 – Locrian

Each mode is built using the the formula from the Major Scale except the ROOT (or the 1) is moved to start on a different degree, like the 2 or the 3 for example. When we shift the starting note, our formula is no longer the familiar Whole-Whole-Half-Whole-Whole-Whole-Half from the Major scale; it becomes a new and unique set of intervals that gives each mode its signature sound.

How Modes are USUALLY Taught (RELATIVE VIEW)

As you can see, the Modes are constructed by taking the Major Scale (Ionian) formula and building a new scale starting off each degree. In other words, we can build a scale using the formula above but starting on the 2 (Dorian). Or another scale using the formula above but starting on the 3 (Phrygian). Or another starting on the 4 (Lydian), etc.

Everything in that diagram is all true, but that is just how the modes are CONSTRUCTED. This is called the RELATIVE view. In the Relative view, we haven’t yet shifted the numbers to match the sound of our new scale.

In Music, the numbers are not just arbitrarily assigned to any note. Each number has a specific sound that we learn to recognize. The numbers represent a particular hierarchy in the stability of the notes within the scale. Most importantly, the Root (or note 1) has to sound/feel like your scale’s Home Note or Center. All of the other intervals must relate back to the 1 as being that ROOT of your scale. You can’t just call your HOME NOTE a 7 or a 2 or a 6.

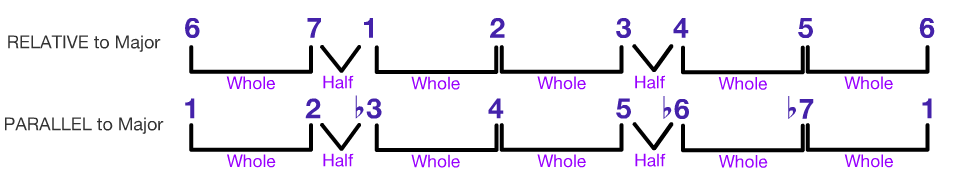

To actually USE the Modes as Modes, we need to relabel each degree so it matches the SOUND of the interval relating back to our new ROOT. If we view the starting note of each Mode as the 1, this is called PARALLEL view. This is where a Mode becomes its own standalone scale.

How Modes Are Actually USED (Parallel View)

As you can see above in the PARALLEL view, we now have a new set of numbers because the intervals all relate back to the first note of the scale as the 1 or Root.

Understanding the concept of RELATIVE VS PARALLEL views of a scale seems to be the big misconception. Again, we have to view the scale starting on its own 1 for it to actually be its own scale or mode.

Aeolian (The Minor Scale) as seen as Relative VS. Parallel

To demonstrate this, you need to HEAR IT, and when hearing these things, it VERY OFTEN comes down to the chords we’re playing over. To help, I am going to play the scale over some chords, and you can magically hear the root change places.

The example below features THE EXACT SAME SCALE, but I have changed the chords behind the scale. In the RELATIVE example, the chords make the scale sound as relative to major (and the degrees will sound like 6 – 7 – 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6). In the the PARALLEL example, the chords will make the scale actually sound like Aeolian (the minor scale), and you’ll hear the first note as 1, the second note as a 2, the third note as a b3, etc…

After you play each example, play the button with the corresponding Root. (Relative Root for the Relative Example, Parallel Root for the Parallel example). They should sound like the tonal center or home note for each example.

To sum up:

In order for something to actually be Modal (its own Mode), we have to see it/hear it as PARALLEL. And yes, very often, the chords we’re playing over will either dictate this or have to be written to suit the mode we are using.

We’ll take a look at how chords affect the Modes in the next lesson.